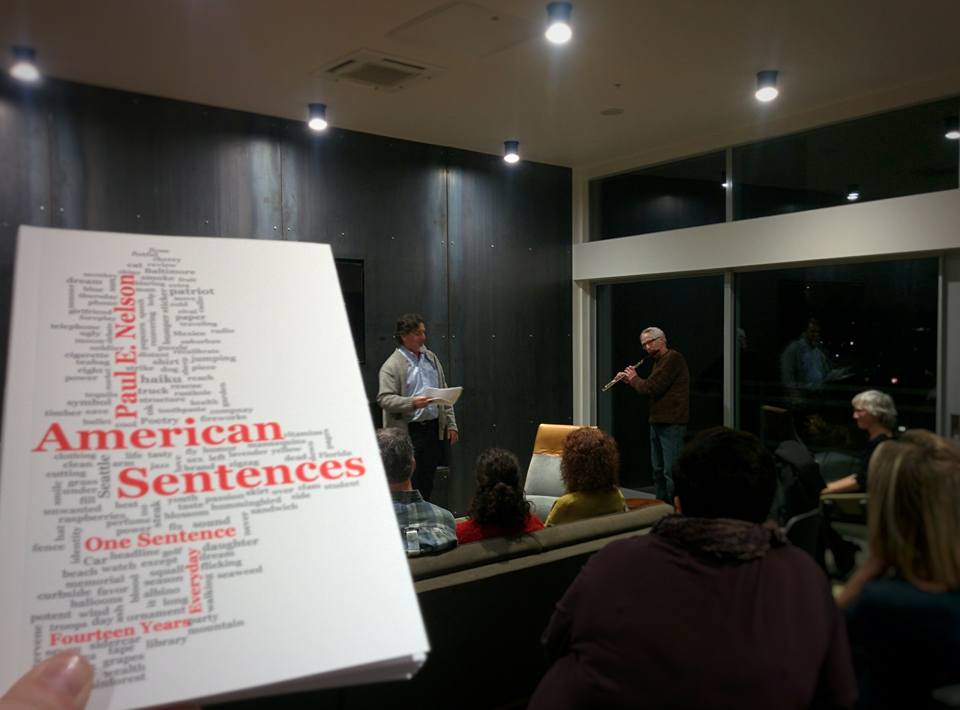

Dec 5, 2015 Photo by Faiza Sultan

(For Columbia City Gallery Literary Series, Dec 13, 2015)

“We study the self to lose the self.

Only when you forget yourself

can you become one with all things.”

– Dögen

Some brief thoughts about my immediate take on the subject for which we are ostensibly gathered. I was thinking about the topic and what I might say as an introduction to my collaborative performance with Jim O’Halloran, my flute-playing Subud Brother, when I decided to get in my daily walk during a rainstorm. The walk was a little less than a mile each way and I was soaked when I returned and had to change clothes it was so intense.

Thought one is poet Louis Zukofsky’s notion that poetry’s lower limit is speech and its upper limit, music. And there is the potential for music in any of the work I do. (Sidebar, I love Nate Mackey’s riffing off Zukofsky: “Poetry is an art whose lower limit is check, upper limit enchantment.”)

And take one simple American Sentence, written during (or after) that rain-soaked walk:

12.8.15 – Walk in the angled Cascadia rain to harvest December chard.

/ u u / u u / u u / u / u u / u /

This is almost perfect Dactylic meter: a stressed syllable followed by two light syllables:

12.8.15 – Walk in the angled Cascadia rain to harvest December chard.

/ u u / u u / u u / u / u u / u /

But of course I am not thinking in terms of meter when I compose, I am thinking of imagery, or juxtaposition of specific images. Yet when music, or listening, is a foundation of the work (this may take decades to internalize) the meter is only part of the music and requires almost no thought to appear in the poem. Notice how the “K” sounds in “walk” and “Cascadia” mingle with the short “a” sounds in “walk” and “CascadiA” and “angled” and then the long “a” sounds of “CasCAdia” and “rain” as well as the “d” sounds in “CascaDia,” December and “chard” mingle with the internal rhyme of “harvest” and “chard.” Ezra Pound calls this melopoeia, or the melody part of verse. Assonance, the similar vowel sounds, are much more subtle (and harder to do) than both end rhyme AND alliteration. The great Canadian poet George Bowering warns about how easy alliteration is and as such, something to avoid in most cases because of that, Peter Piper you pooty parper.

And when collaborating with a musician like Jim, he is listening for the content, for the tone of the words. A poem about a couple burning up in bus, for example, is going to get a different treatment (tone) than a poem about leftover stuffing or cat shit. Jim also listens for rhythm and other factors.

I could take almost any of my poems and point out the assonance, as that seems to come with the territory of being an intense listener, but it is important to note that listening is the key to composing verse in the spontaneous/projective/organic manner. It may very well be the music, and the precise naming, which allows us to forget the self in the moment and tap in to the “other.” May be the Muse, may be the morphic resonance of the place, as Rupert Sheldrake would say or maybe even dead poets as I suggest in the last poem in A Time Before Slaughter, who may provide metaphors for your verse while scaring garden raccoons, but all good art that comes from the depths of one’s soul, “jiwa” in Javanese, transcends the self and taps into that “other.” This is why people are hungering for so much more than what entertainment gives them and why they are often disappointed by what passes for “art” because the poet refuses to go further down one’s own throat to the place where all things meet.

And always in deep listening there are echoes of Kuan Yin, the Water Bodhisattva, or “She-Who-Perceives-the-World’s-Cries.” The more we can lose the small “s” self, the more we can experience the large “S” self and the human in us becomes a little more noble. (I think this was lost in North American poetry when LANGUAGE poetry then Conceptual poetry became the favored “avant-garde.” Track something larger than you, larger than a theory, and some beautiful things can emerge.) Composing with an understanding that tracking the music syllable by syllable can be a learning experience, a self-deepening experience. Denise Levertov who lived not far from this spot the last several years of her life said the poem’s “form is never more than a revelation of content.” Often the content revealed is a clue to one’s personal mythology and as Dögen says “you study the self to lose the self.”

And in performance, all this music comes and goes so quickly. Listening to a recording of the performance one can get more of the music and reading the American Sentences in the book, one can slow it down to one’s own pace and see the subtle “music at the heart of thinking,” as poet Fred Wah put it, may just deepen your appreciation of the work. But just having the experience of the poem, or the song, giving it the gift of your presence, is all a poet or musician can ask of a reader or audience member.

pEN

4:12pm

12.13.15

Dec 5, 2015 photo by Emiliana Chávez

0 Comments